Seeking to redefine the art museum as a demotic meeting place rather than elitist treasure house, Steven HolI’s long awaited Museum of Contemporary Art in Helsinki fuses rich interior mystery with a bold urban context

Originally published in AR August 1998, this piece was republished online in September 2011

Chiasma - derived from the Greek letter chi and meaning a crossing or exchange - was the code word used by Steven Holl to identify his 1993 competition entry for the new national museum of contemporary art in Helsinki (AR October 1993). Although more often related to anatomy or genetics than architecture, this borrowed term is, in Holl’s own words, the conceptual underpinning of the scheme, ’ … the joining of interior mystery with exterior horizon, two hands clasping, the architectonic equivalent of a public invitation’.

The new museum in its Helsinki context. The site lies to the south of Toolo Bay, with Finland’s Parliament Building to the west.

The adoption of the Finnish translation, kiasma, as the permanent name of the completed building is testimony to Holl’s perceptive reading of the brief, the site, and perhaps most importantly, the Finnish psyche.

The new building seeks to redefine the art museum as an institution, shifting from the image of elitist treasure house to public meeting place. A catholic collection, a wide range of events, and extended opening hours are intended to attract the widest possible audience. The site for the new building is well situated to support the idea of art as a medium for public interaction. Bounded on the west by Mannerheimtie, a major vehicular route into the city centre, the sloping triangular plot is surrounded by significant public and cultural institutions: Parliament and the National Museum to the west, Aalto’s Finlandia Hall to the north, and Eliel Saarinen’s Helsinki Station to the east.

South elevation. The fissure between the two parts of the building is marked by an extended entrance canopy

A statue of Marshal Mannerheim, the father of modern Finland, is located on the site near the west boundary. Although centrally situated, the site is the southern most tip of a large under-used area of land - the residue of the confluence of two city grids, rail yards, and Töölö Bay. Over the years, the area has been the subject of numerous urban planning proposals. A 1964 scheme by Alvar Aalto connected Töölö Bay to the city with a series of public terraces and lined its west shore with cultural institutions; regrettably, only Finlandia Hall was realized. HolI’s competition entry proposed the extension of Töölö Bay south to the museum site, underscoring once again the critical role this part of the city can play in connecting culture with nature.

The scheme comprises three elements: a bar of water and two bars of building.

From the south, the building appears as an aggregation of crisp, geometric forms with the popular statue of Marshal Mannerheim on the far left.

By pushing the building tight to the east side of the site, a new piazza with a long reflecting pool is defined for the statue of Mannerheim adjacent to the street. The western building is orthogonal while the eastern bar, a twisted curvilinear form, is sheared off on its south and east faces as it comes into contact with the grid of the city. At the north end of the site, the three bars intersect. The open end of the curvilinear volume becomes the dominant form reaching out to the natural landscape. In contrast with the sheer south elevation, the deeply carved north façade records the many geometries exerting an influence on the site. The water crosses through the body of the building and falls to a small pool at lower ground level, a gesture towards the connection between the reflecting pool and the extension of Töölö Bay envisioned in HolI’s competition scheme.

The glazed, truncated end of the curved volume

Vehicular access for parking and deliveries is discreetly tucked away at lower ground level together with museum workshops, storage and mechanical plant rooms. This enables upper ground level - the level of the city centre - to be given over entirely to freely accessible public facilities. Staff offices, cloakrooms and a 230-seat auditorium are on the east side of the building, and to the west are the information/ticket desk, the museum shop and a cafe which opens out onto a public terrace and the reflecting pool.

The museum entrance at the south end of the building is approached across a granite paved forecourt designed by Juhani Pallasmaa. A steel framed glazed canopy extends out from the vertical fissure between building bars to draw visitors to the entrance.

“The new building seeks to redefine the art museum as an institution, shifting from the image of elitist treasure house to public meeting place”

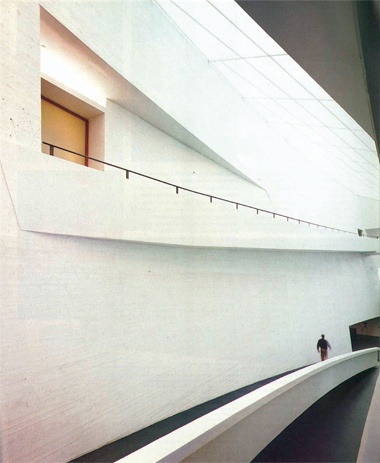

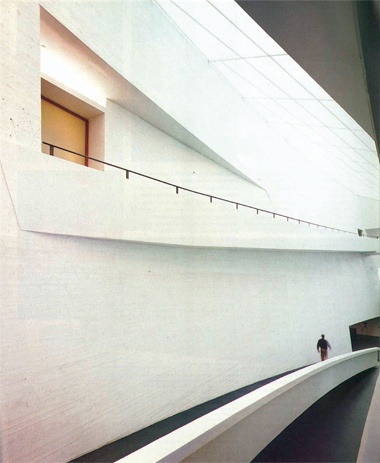

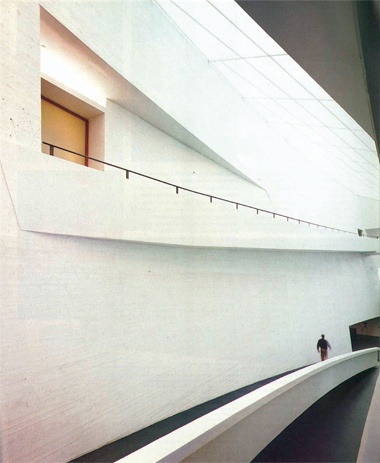

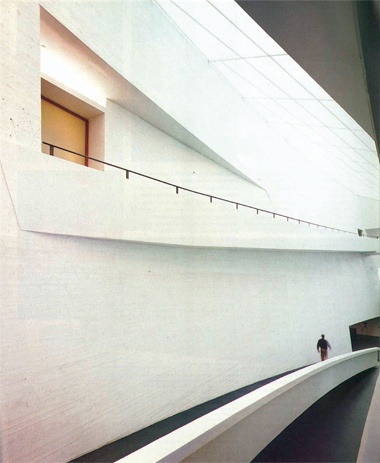

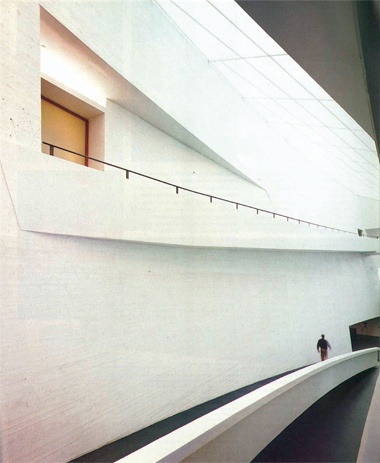

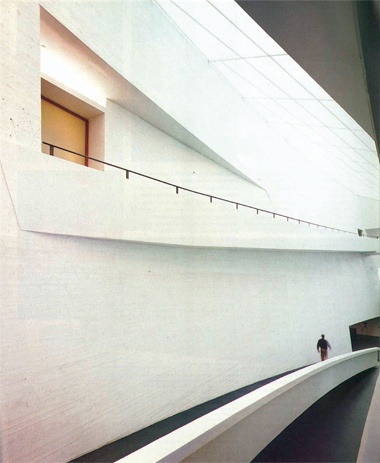

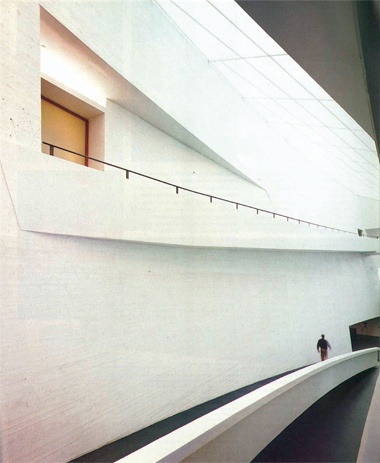

The outwardly modest demeanour of the entrance facade provides an excellent foil for the interior drama of the slender, elongated warped void which defines the heart of the museum. A ramp climbs up the curved east wall of the void, arriving at the critical crossing point of the bars of building and water. The first level of galleries is entered from this landing. Suites of enfilade double-height galleries step up the building in four split levels on alternating sides of the central void. Exhibitions of the permanent collection - to be rotated annually - are housed in the lower galleries, and changing exhibitions are on the upper levels.

The underlying order of the building cannot be understood from a single vantage point, but unfolds cinematically as you move through a landscape of interior space. This is an architecture of promenade, yet without a prescribed or privileged route. Multiple lifts, stairs and ramps combine with the split-level galleries to create many possible itineraries. Passage between rooms - never axial - occurs on the diagonal, in a zigzag trajectory, or within a double-height rooflit aisle tight to the curved north-eastern facade of the building. Circulation always returns to the central orienting void.

Part of the svelte, curvilinear volume

While HolI is interested in the fluid character of space, the complex curvature of the eastern wall of the inner void between the two building volumes is more than a wilful formal gesture. It is a pragmatic move to capture the elusive horizontal light at this northern latitude. Shaped in plan to mirror the arc of the winter sun, the wall also rotates from a 9.5 degree outward tilt at its southern end to 9.5 degrees inward at the north. In addition to catching light, the curvature works well in urban terms. The north end of the building twists towards the west, acknowledging the adjacent cultural institutions and framing the new exterior plaza.

Each of the 25 galleries in the building is unique in both form and quality of light. Spaces in the west bar of the building are orthogonal, while those in the east bar are less regular. The lower level galleries have flat ceilings and receive daylight through the translucent curtain wall. Moving up through the building, the horizontal ceiling datum is eroded to become ever more sculptural in section. Deep shafts carved into the curved profile at the north-east end of the museum bring sky light unexpectedly into the middle level galleries. The uppermost gallery at the north end of the building is a dramatic toplit vaulted space.

Voluminous first floor gallery

Much of the daylight in the building particularly in the galleries and the central void - is diffused by translucent glass which both intensifies the weak Nordic light and imparts a sense of quiet abstraction and detachment from the life of the city. So movement through the building becomes an introverted journey. Release in the form of views out is provided by clear glazing at significant points - at the north and south ends of the building and the crossing. The slender vertical slice of city viewed out of the fissure in the south facade contrasts with the sweeping panoramic vista looking north. A generous expanse of clear glass where the building volumes intersect on the west facade both reveals interior vertical movement and augments it with ever changing dappled sunlight reflected from the horizontal surface of water. In contrast, on the east facade, a small crescent window allows a glimpse of the railway station and marks the juncture between orthogonal and curvilinear form as well as the change of ground level on the site.

As important as daylight is in this building, it cannot be relied upon at this extreme northern latitude. Indeed, with the museum open daily from 10am to 10pm, there are many months of darkness. Each gallery therefore has two sources of artificial light - fluorescents concealed by light shelves, and flexible demountable spotlights in a 1.2 metre flush ceiling grid. The many configurations of warm artificial light and cool natural light enrich the experience of these spaces. At ground level, lighting is less mysterious and the desired effect more calculated. The low ceiling of the dark cloakroom is warmed by the glow of red and yellow stained plywood fittings. In contrast, the high red oxide-coloured ceiling of the brightly daylit cafe is punctuated by blown glass fittings intended to evoke an image of melting ice.

Gallery on the topmost floor. Roughly plastered white painted walls and black dyed concrete floors are transmuted into subtle, painterly composition in shades of grey

Concealment of lighting in the galleries is indicative of a larger strategy to eliminate mid-scale detail to create spaces which focus attention on the art rather than the building. The hybrid concrete and steel framed structure is concealed within 600mm thick wall zones. Likewise, servicing is discreet. Air is supplied through flush perforated steel floor grilles, and extracts hidden within the light shelves connect to return plenums within the thick walls. Skirtings and mouldings are eliminated. In the central void, where there is no art, the horizontally banded walls are of board-formed in-situ concrete. This subtle distinction of texture, with the thin black line of the steel handrails, provides an understated intermediate scale of detail, a transition from the bright, lively public spaces at ground level to the quiet galleries above.

The palette of gallery finishes is carefully judged in this game of abstraction. Animated by light, roughly plastered white painted walls and black dyed concrete floors become pure painterly compositions in shades of grey, eerily like Steven Holl’s watercolours for the project. Acid-reddened brass - always used as a thin face-fixed patchwork veneer - marks significant cuts through the building volumes, notably the automatic sliding glass entrance doors which isolate the galleries environmentally from the central void and linings to the openings between galleries.

Kiasma does not dazzle, but rather - through the quiet juxtaposition of light and dark, white and black, curve and straight line - is an essay in subtleties

As a marker of significant cuts, the reddened brass plays a similar role externally where it is used to clad the main south entrance, the north facade, and the exterior water course and pedestrian path which slice through the building to connect the two ground levels on the site. Apart from these incisions, the building is as muted and cool outside as it is within. The double curved east wall of the void is expressed externally as a wall of translucent glass planks. Vertical surfaces are sheathed with a rainscreen of aluminium panels combined with glazed curtain walling, and the curved north-east end of the building is clad with pre-patinated zinc. On a cloudy day, the building takes on the leaden hue of the sky, but with even a ray of sunshine, the glass and aluminium skin becomes an active surface of muted light. By night, the reticent character of the building is transformed. Lighted from within, the museum becomes a lantern - a glowing collage of shades of white created by the many combinations of clear and translucent glass - that promises to be particularly mysterious in the winter snow and fog.

The elimination of mid-scale detail imparts an intentionally rugged, workshop-like character to the building. This works best where the rough edge of the concrete slab is silhouetted against the precision of the curtain wall or where the surface of the machine-made aluminium cladding is animated by hand sanding. It is less compelling in other areas: for instance, numerous flush services access panels in the plastered walls of the galleries are distracting. Although much care has been lavished on the purpose designed lavatory fittings, associated electrics are unresolved. Carefully considered, the patina of time could enrich the phenomenological experience of the building; yet, the stripped down aesthetic already looks worn in places.

Kiasma expands upon a number of themes of Steven Holl’s earlier work. Although enmeshed in the fabric of both city and nature, the building also has a figural, iconic quality. Hinge space is operating at many levels, from the conceptual place of the site in the city to the detail of the entrance into the museum shop. The multifarious effects of light - richly coloured in the Chapel of St Ignatius (AR August 1997) - are here monochromatically rendered. Likewise, the tension between the stone and the feather persists; materials serve visual and tactile purposes but are detailed to suppress dimension and weight.

The interior drama of the elongated, warped void, articulated by slender silvers of handrails

This building also inevitably draws Steven Holl into the context of Alvar Aalto. In addition to obvious formal affinities and shared contextual preoccupations on this particular site, Holl’s tactile sense of detail could hardly find more distinguished precedent. Aalto’s ‘methodical accommodation to circumstance’* resonates in Holl’s notion of the intertwining of site, circumstance and idea. Aalto’s architecture reflected the complex character of a newly independent nation forging an identity coupled with an underlying mystical, almost primeval communion with nature. A generation on, HolI’s ‘fresh chiasma of phenomenal architecture’ is well matched with this duality; the new museum is as much mythical narrative as national monument. Kiasma does not dazzle, but rather - through the quiet juxtaposition of light and dark, white and black, curve and straight line - is an essay in subtleties. The reticent way in which Kiasma unfolds to reveal itself, joining interior mystery with exterior horizon, is a perceptive reading of both Finland and its people.

*Anderson, Stanford. ‘Aalto and “Methodical Accommodation to Circumstance” ’, Alvar Aalto in Seven Buildings, Helsinki, Museum of Finnish Architecture, 1998, pp 143-149.

FACT FILE

Architect Steven HolI Architects, New York

Project team Steven HolI, Vesa Honkonen, Justin Russli, Chris McVoy, Janet Cross, Tomoaki Tanaka, Pabo Castro-Estevez, Justin Korhammer, Tim Bade, Anderson Lee, Anna MUlier, Tapani Talo, Lan Kinsbergen, Lisina Fingerhuth

Associate architect Juhani Pallasmaa

Structural engineer M.Ollila

Services engineer Olof Granlund

Electrical engineer Tauno Nissinen

Structural and mechanical consultant Ove Arup & Partners

Lighting consultant L’Observatoire International

Photographs Paul Warchol

Architectural Review Online and print magazine about international design

Architectural Review Online and print magazine about international design